Nothing quite beats board game night in my house. I love board games like Settlers of Catan. Players develop the mythical island nation by collecting resources to build roads and dwellings to amass victory points, the currency of Catanian competition.

Catan is a bit like chess. It has fairly simple rules, and its structure of play is straightforward. Yet there is enough complexity to make the game ever more interesting with repeated play.

I’ve introduced friends, neighbors and my daughters to the game.

However, I do have a pet peeve. It relates to the way people talk about the dice.

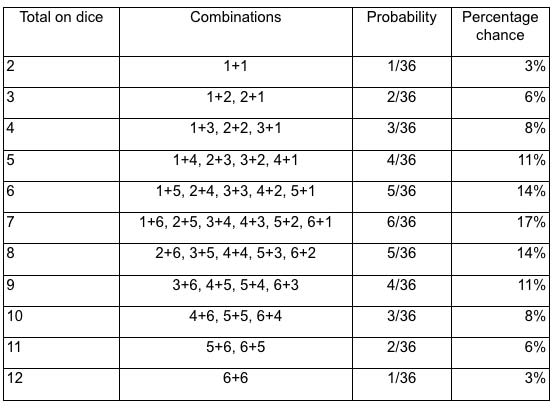

The rolling of dice generates the game’s currency — resources like wheat, sheep, bricks, ore and trees. You need these resources to build, and ultimately win, the game. Ideally, you want to position your settlements next to eights and sixes because they are more commonly rolled than twos and threes. (In case you’re wondering, here are the odds with each roll of two dice.)

Yet players will sometimes select fours, fives or tens because in the last game “Tens were hot.” Or “Fours killed me last time … not again.”

I have nothing against those numbers. (After all, I was born on the fourth!) But assuming we’re not playing with loaded dice, the odds are always better that the next roll will be a six or eight. Always.

Never a nine, four, five, two or three.

No matter what was rolled in the last ten, twenty, fifty or one thousand past rolls.

When I play with my kids, it’s my duty to emphasize this point. Not because I want them to dominate the Catan circuit, but because I want them to think accurately about odds.

Believing that previous rolls influence the subsequent ones is an example of mistakenly thinking something possible is probable. It’s possible, but not probable, that we’ll see a bunch more nines than eights in the next game or even the rest of a current game.

We humans are pattern recognition machines. We see a string of nines and naturally expect to see more nines.

We all have many biases, and I want my kids to be aware of them.

Bias awareness is relevant to not only Catan but also investing (and frankly to life). I’m not an investing expert. Like you, I’m just a parent trying to raise my kids to be smart with money. And kids are going to ask their parents about money and investing.

When my daughter asked me if she should sell the first three shares of stock she ever purchased because it had tripled in value, I said, “I don’t know. Do you think you should sell?”

She glared at me.

So I shared with her that I bought Apple two decades ago at roughly $60 and sold it after it had tripled in value. Since then, of course, it has gone up about a gazillion percent.

Had I been aware of another human bias — that we try to avoid losses at all costs, otherwise known as loss aversion — I might have made a different choice.

Perhaps I might have researched whether Apple was then a company worth its $180/share price. Was there apparent opportunity for it to grow from there? Had I looked a bit more closely, maybe I would have seen it.

Not being aware of my bias meant I made a less informed decision.

“So I shouldn’t sell it?” She wondered.

Then I told her about a $2,000 investment I’d made in a company based on a recommendation. Within two years that money evaporated. I emphasized the result with flair:

“GONE!”

Aside from the apparent take-home messages from these two stories — be wary of following dad’s investing advice and dad likes qwanswers (answering questions with questions) — there’s a more explicit lesson to learn.

I told her there is simply no shortcut to picking individual stocks. You need to do the research when you buy and sell, and you need to understand that there is always risk involved.

Jason Zweig, The Wall Street Journal’s “Intelligent Investor” columnist, alerts us to a critical point in his book Your Money & Your Brain: “We are intuitively poor investors.” It’s hardwired into us.

To top that off, we tend to be overconfident, see patterns where there is randomness and think we’re better investors than your average Joe. Yep, another bias — the base rate fallacy.

So when I talk about intelligent investing, I mean that our starting point is obvious:

We are born stupid investors.

We must learn how biases cloud our thinking and, through personal experience, discover how active we are willing to be with our investments.

I took a second to explain to my daughter that’s why we have most of our money in various index funds, collections of stocks that track standard market indexes. We’ve realized that we’re not interested in doing the intense research required to invest the lion’s share of our portfolio with individual stocks. Instead, we choose from index funds for small companies, large companies, international companies and many more. Doing so gives us access to a diverse range of stocks and reduces risk by mitigating human choice and the bias that informs it.

Even the most famous stock picker of all, Warren Buffett, advises everyone to invest in index funds. “The trick is not to pick the right company,” Buffett told CNBC’s On The Money in 2017. “The trick is to essentially buy all the big companies through the S&P 500 and to do it consistently.” Buffett’s quotable partner, Charlie Munger, adds, “The first rule of compounding is to never interrupt it unnecessarily.”

I told my daughter that she might want to consider what her mom had just done — selling off the recently skyrocketed Tesla stock to cover the amount we’d already invested. My wife’s action is in keeping with the advice in a New York Times article: “Set a limit on gains in any stock. Once past that point, sell enough to capture all the winnings and put them in a basic index fund.”

And yes, I told her I might have been better off considering this approach with my Apple stock.

I left my daughter with these bits of advice:

- Start Small. You can only learn your interest in individual stock picking and risk tolerance through experience. As the saying goes, “Personal finance is more personal than finance.” Get to know your biases. Mistaking possibility for probability and seeing patterns in randomness are two of them. For more, read Jason Zweig’s book. And remember, all of us can’t be above average.

- Mad Money! Jason Zweig advises that you have a “mad money” account of no more than 10% of your invested cash for speculative investments. You can use this account to discover your biases, determine how much risk you’re willing to take and make mistakes without jeopardizing the lion’s share of your investments.

- Mom Knows Best. Mom makes intuitively better decisions than Dad, maybe because she’s more in touch with her biases. (In case you’re wondering, I made sure this essay met with my wife’s approval; she is the investing OG of the family.)

I hope you now have a better sense of how to raise intelligent investors.

I have to wrap things up here. It’s time for another game of Catan, and I want to make sure I get some sixes and eights.

John

PS If you’re interested, the SEC has an excellent free primer on index funds.

I want to thank the following people for their contribution to this essay: Erin Prim and my friends at Foster: Doc Ayomide, David Burt, Stew Fortier, Chris Harvey, Alberto Sadde and Tom White.